Implement App Maintenance Mode with...

November 25, 2025

The Python 3.11 changelog is a seemingly unending collection of bug fixes, improvements, and additions, the majority of which you may never discover. However, a few crucial new features may significantly improve your Python process when the stable release arrives.

Here’s a rundown of the most significant new features in Python 3.11 and what they mean for Python developers.

The first big change that will thrill data scientists is an increase in speed—the usual benchmark suite now runs around 25% faster than in 3.10. According to the Python documentation, 3.11 can be up to 60% faster in some cases.

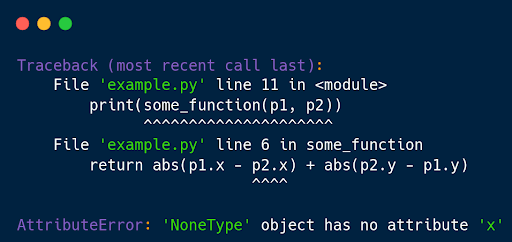

Another immediately useful feature in Python 3.11 is more detailed error messages. Python 3.10 already had better error reporting, thanks to the new parser used in the interpreter. Now, Python 3.11 expands on that by improving error message that pinpoints the specific location of the fault. Rather than returning a 100-line traceback that ends with a difficult-to-understand error message, Python 3.11 points to the expression that produced the error.

In the preceding example, the Python interpreter refers to the x that caused the script to fail due to its None value. Because there are two objects with the ‘x’ attribute, the error would have been unclear in current Python versions. However, 3.11’s error handling clearly identifies the faulty expression.

This example shows how 3.11 can identify an issue in a deeply nested dictionary and clearly identify the key the error belongs to.

Read more: Everything you need to know 3.11

“Explicit is better than implicit.”

The preceding text is the second line of the Zen of Python, which is a list of Python’s 20 design principles. This is an example of the rule that Python code should be as expressive as feasible.

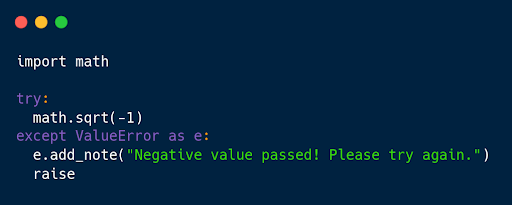

Python 3.11 includes exception notes to emphasise this design approach. (PEP 678). When you raise an error, you may now call the add_note() function inside your unless clauses and give a custom message.

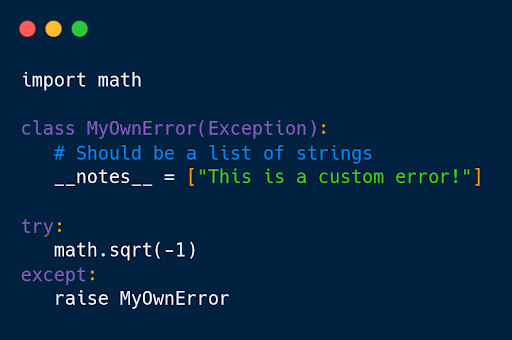

If you have written a custom exception class like below, you can add multiple notes to the class inside the protected class-level attribute __notes__:

Statically typed languages aid in the readability and debuggability of your code. Defining the exact kind of variables, function inputs, and outputs can save you hours of debugging effort and help others read your code more easily. Adding typing annotations will also allow modern IDEs to display function definitions as you enter their names, making your functions easier for others to understand.

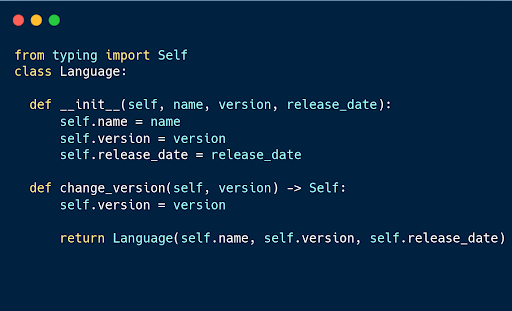

Until now, Python’s strong typing module provided classes for almost any data type, except for classes that return instances of themselves.

However, Python 3.11 provides the Self class, which you can include in the declaration of a function if the function’s return value is self or a new instance of the class itself.

There are a few other quality-of-life improvements to the standard libraries. First, two long-awaited functions are added to the math module. It’s remarkable that it took Python 28 years to include the cube-root function, but as the phrase goes, better late than never.

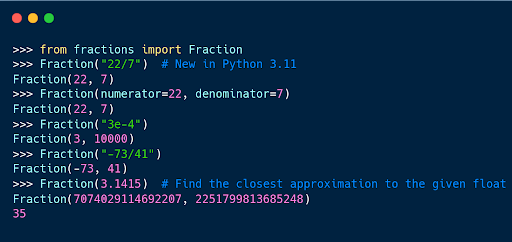

A new feature in the fractions module allows you to build fractions from strings:

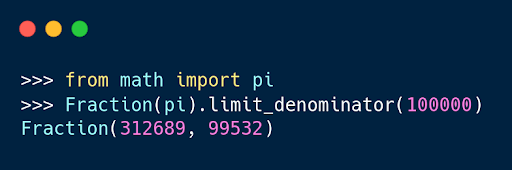

As you can see, the fractions module is useful for some arithmetic operations. I particularly enjoy how you can get the fraction that is closest to the supplied float. You can go one step farther by specifying a denominator limit:

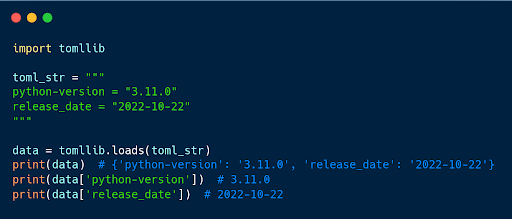

There is also a new tomllib module for parsing TOML documents. Tom’s Obvious Minimal Language (TOML) is a common file format for creating human-readable configuration files.

Python uses TOML, or Tom’s Obvious Minimal Language, as a configuration format (as in pyproject.toml), but doesn’t expose the ability to read TOML-format files as a standard library module. Python 3.11 adds tomllib to address that problem.

Note that tomllib doesn’t create or write TOML files; for that you need a third-party module like Tomli-W or TOML Kit.

One of Python’s strengths in its early days was that it came with batteries included. This somewhat mythical phrase is used to point out that a lot of functionality is included in the programming language itself.

However, the real batteries are available in Python’s standard library. This is a collection of packages that come included with every installation of Python.

In total, the standard library consists of several hundred modules:

You can see which modules are available in the standard library by inspecting sys.stdlib_module_names.

Over time, the usefulness of the standard library has diminished, primarily because distribution and installation of third-party modules have gotten much more convenient. Many of Python’s most popular features now live outside the main distribution. Data science libraries like NumPy and pandas, visualization tools like Matplotlib and Bokeh, and web frameworks like Django and Flask are all developed independently.

PEP 594 kicked off an effort to remove many so-called dead batteries, or modules that are obsolete or unmaintained, from the Python standard library. As of Python 3.11, those libraries are marked as deprecated but not yet removed; they will be removed entirely in Python 3.13.

A new release of Python is always cause for celebration, and acknowledgment of all the effort that’s been poured into the language by volunteers from around the world.

In this blog, you’ve seen new features and improvements like: